Michael Punt, Martha Blassnigg, David Surman – From Mélièse to Galaxy Quest: The Dark Matter of the Popular Imagination – 2004

First publication workshop Space: Science, Technology and the Arts in collaboration with ESA/ESTEC, 2004

Introduction

MetaTechnology Research is a research center in the University of Wales, Newport. It inquires into the metaphorical, metaphysical and metadiscursive aspects of technology by integrating a range of scholarly activities and amplifying them through non-hierarchical collaboration within an institutional environment. It combines the research of artists, filmmakers, photographers and designers with the aim of advancing our understanding of the history of technology and exploring new modalities of academic and practical research. This paper (by the three authors) deals with the particular aspect of our research at Metatech Research which deals with technology and the human imagination and constructs it as a mirror image of space. At least in the sense that it is largely unknowable and all that we can ever say about it as an entity is based on conjecture drawn from our fragmentary perception the wake of its apparently infinite energy.

As a methodology, (to flatter our fumbling) we study the visible residue of the human imagination in the arts, science and technology and modestly extrapolating the network forces that seem to intersect at their instantiation, aware all the time that we are always describing, and never – except in lapses of modesty – never explaining. For this group of researchers our common point of departure is cinema; a technological anachronism that caught the public imagination in ways that initially no scientist, inventor, technologist, entrepreneur or showman ever predicted. The exception to this is possibly the conjuror Georges Mélièse, and a few British eccentrics – mediums, showmen and instrument makers.

Mélièse of course is well known in space research for making the first space movie, and given more time we would show one of his many versions of it as evidence not simply of the technological imagination (indebted no doubt to Jules Verne) but also of the residues of the very antagonistic energies that stimulated the enthusiasm for cinema. Instead I will begin with perhaps a less familiar film, The Big Swallow, made in 1900 by the British film-maker James Williamson.

The Big Swallow was made at a time when, for metropolitan audiences at least, moving pictures were becoming familiar, and at a time when the cinematographer filming a busy street – sometimes even the venue of a forthcoming seance, was also becoming a commonplace. As the voice over tells us, we see an ordinary man become so irate at the ubiquitous photographer that he swallows him up camera tripod and all. After his mischief he backs off from the cine camera smacking his lips and hams up the joke for the audience in a gesture of mutual conspiracy. Its a simple gag film manifesting an antique humour, but in our view, it would be a mistake to see it simply as a school boy joke, since although there is a displacement from the cinematographe to the still camera the film is nonetheless suggestive of a certain unease even antagonism in the gap between a photographic technology which is used to represent the world and those who look at its representations. This particular disaffection is elegantly summed up to some extent in the conspiratorial gesture as Williamson’s actor digests the machine which represents him-takes into the dark matter of the interior body. It is a sentiment which, judging by our own cinema has not gone away as we see a recirculation of both a celebration and a covert criticism of digital science in popular movies like Jurrasic Park, Barb Wire, Twister, Mission Impossible, and as we will hear in a moment Barbarella. This theodicy – the coexistence of apparently contradictory dynamics in a coherent reality provides our first piece of evidence that the imagination is dark matter that is manifest to our intelligence in its various instantiations as a complex intersecting network forces. 1

Desire, Imagination and Technology: how to love (in) Space [2]

Dark matter of still unexplored mystery of the universe and our yet inexplicable human brain capacities seem to stand in no relation to the rather small amount of scientific knowledge. This void constitutes a perfect platform for imagination and fantasy within popular culture and offers a plane for metaphysical and imaginative inquiry. In a spiritual context, this darkness and void has mostly contradicted the imagination of divine light and the spiritual imaginary crowded with heavenly creatures, yet there exist notions that relate the invisible divine light to darkness. [3] In space (and time) travel, the space craft and the angel both have conquered and colonized outer space in our human attempt to overcome our three dimensions via spiritual and technological media. While technology has turned wireless, angels have become wingless [4] and present themselves in contemporary clairvoyant perception as rather abstract light beings similar to auroras. The angel as a symptomatic concept exceeds its religious connotations and turns into an intercultural, interconnecting, service-oriented, mobile, flexible, genderless and ubiquitous mediator. Traveling through and beyond time and space, it becomes attributed with characteristics that could as well be applied to contemporary communications technology and its more and more immaterial devices.

Next to the dominant expressions of fear and destruction confronting alien space in most mainstream movies, more constructive imagination has been projected and reiterated in popular subcultures since the technological venture of space travel in the 50s. Cinema forms a technology that expansively has picked up metaphysics and imagination and constitutes the perfect medium to explore space and time in both, content and its medium, in a scientific as well as a science-fictive way. Studying similarities between the cinematographic experience and human imagination, [5] Edgar Morin mentions how cinema offers a symbiosis that integrates the spectator in the flux of the film, and the film into the psychical flux of the spectator. [6] Cinema, the dream-machine or time-machine, and « homo demens », the producer of fantasies, myths, ideologies and dreams, both evoke magic as interiorised quality through affection. When Alberti (1404-72) invented the linear perspective of depth with a vanishing point, Robert D. Romanyshyn argues, the inexplicable has moved inside and became an interior quality of imagination. This new perception not only moved angels and demons out of heaven and clouds onto the same horizontal plane in paintings, but also prepared for the imagination of space travel. [7]

Cultural expressions in various media productions are indispensable not only to illustrate but to justify scientific technological venture. [8] In this sense it has repeatedly been argued how important it was that the moon-landing in 1969 has been transmitted through film images in order to touch, involve and convince a broad audience. [9] The unlimited outer space offers an open platform to express our imagination and reflects like a 360 degree three- (or maybe more-?) dimensional screen or plane, inviting not merely to an audio-visual performance, but to a multi-sensorial event and engagement that includes the body [10] and our consciousness as equal faculties. In what follows I will speak about the idea of space travel as an instantiation where imagination, desire and technology meet and interact in one particular appearance in popular culture that persisted historical change through its reiterated popularity: the story of Barbarella.

The SF-movie Barbarella, [11] based on a French comic strip by Jean Claude Forest from 1962, and released in 1968, launches desires and imagination related to the political agenda of the 60s into a space comedy. Sexy, playful, humorous, ironic, erotic, fantastic, political… Next to all its outspokenness, directness and frankness in matters around sexual desire and utopian technology, it also plays with a rather concealed desire of a quest for innocence and restoration of an ideal world, bound into ecological, democratic left wing concerns and dreams of the 60s movements.

Coincidentally, Barbarella is currently celebrating its world premiere as musical, [12] advertised as sexy rock-musical in Vienna. Barbarella, the sexy space agent travelling in outer space, this time has to save her crew on planet Sogo and again, with the help of the angel Pygar, she gains victory over the Black Queen who tries to seduce her. In the reception room of the Raimund Theatre in Vienna where the musical is shown, the Italian coffee trademark « Lavazza » exhibits their « 2004 mission to Espresso » calender photographs by photographer Thierry Le Guès, referring directly to Barbarella. [13] Lavazza’s public photo contest « Espresso, space and time » has produced a series of portfolios centred on coffee, space, desire and imagination and reflects the public’s affinity with the subject of (outer) space. At the same time, the centre for architecture in the Museums Quartier in Vienna presents the exhibition « The Austrian Phenomenon », a review on the 60s neo-avantgarde architecture that surpassed the limits of physical construction and became a medium for concepts on the exploration of space. In a transfer between technology, art, pop and architecture, experimental projects displayed a technological optimism in their futuristic visions. Event and play modulated temporarily the meaning of the body in urban spaces and presented constructed extensions of consciousness, « …a space travel, like astronauts, but into inner space ». [14]

These three contemporary examples of the very common practise of cultural reiteration and simulation show the complexity of interrelated references and a certain exoticism in the treatment of the subject of space-travel. By transposing it into a framework of comedy, this displacement allows unlimited imagination to expand and explore the desirable otherness of the unknown. In this example, it is by projecting human desires into a scientific venture, that the gap between popular culture and the scientific community is seemingly being decreased. As the popularity of the cult movie Barbarella shows, audiences are still responding to this mechanism and carrying it forward into future imagination. [15]

A brief case-study: The angel and its relation to technology in Barbarella

The interior of Barbarella’s cosy spacecraft, where she performs her famous striptease [16] at the very beginning of the movie, presents an analogy with the angel Pygar, its feathered wings and cosy nest that serve Barbarella’s pleasures. Both the spacecraft and the angel Pygar serve as extensions of our human physical and mental capacities and travel through space; when Barbarella’s spacecraft is out of function, Pygar takes over and transports her to her destiny, the palace of Sogo. Even though the angel Pygar is shown with an anthropomorphic shape, attributed with an attractive masculine body with wings, it is treated like an object by the inhabitants of the city of darkness. Consequently, Pygar’s appearance and blindness remind of a machine, a hybrid form between cyborg and human in space, slightly like Data in the Star Trek Next Generation series. [17] In this view Pygar is an angelic machine that extends Barbarella’s capacities, being operated by her: Barbarella heals Pygar of its inability to fly by making love to it, which could be read as a reparation or restoration of its functioning, and it’s wings are treated like a mechanical extension of it’s body. [18] The angel’s superhuman capacities are not only in, at and of service for Barbarella, but seem to be under her control.

At first sight, Pygar opposes technology in its traditional sense by its human-like appearance and its incorporation of virtues like love and empathy, but at the same time it forms an analogy to the many erotically shaped and attractive machines in the décor on the planet, forming an organic part, connecting technology with body shapes and connoted physical desire. A comparison between the movie and the musical Barbarella reveals this relationship in the crucial love-scene of the story: in the movie, Barbarella makes love to the angel Pygar, who then regains its will to fly. Here Pygar only wears feathered pants, whereas in the musical it is covered with an armour-like outfit, covering its muscles. Apart from its more machine-like appearance, the musical rather relates to the original comic series in this respect, where Barbarella doesn’t make love to Pygar but to the robot Victor instead: a metallic cyborg, a « love-machine ».

The 60s cultural production has most prominently expressed how technology itself can serve as a medium to produce sensorial experiences: Physical pleasure is achieved by Duran Duran’s pleasure machine that at the same time should destroy Barbarella, eternal and Divine love instead is being evoked by the angel Pygar who finally embraces both, the hero Barbarella and the wicked Dark Queen. Pygar wears wings, Barbarella is armoured; together they incorporate forces that enact on the desires projected on the imaginary of technology and spirituality. It seems as if they both needed each other, humans and angels, humans and technology, hand in hand, even in love, in physical union to explore dark matter, confront alterity and re-establish order in the universe. [19] When Barbarella curls into Pygar’s protecting arms at the very end, accepting the union in this love together with the Black Queen, she seems to be transformed into a child, a being beyond sex, regaining her very own innocence. Sex served as a medium to relate with the unknown and alien environment and encounters, now the universe and her body are reconciled and she returns to earth where physical sex has long been transformed into a telepathic orgiastic ritual.

The contemporary reiteration of these attributes and Barbarella’s image-culture expresses not only the unchanged profound human desire to explore the unknown, but also evokes metaphors of the metaphysical in scientific space and the desire to explore experiences in a multi-sensorial and sensuous instead of purely virtual or scientific environment. In this context, the angel serves as a metaphysical model that operates as a screen for projections of human desire and imagination of super-human capacities. As we have seen, in Barbarella, both spirituality and technology are interrelated and interconnected. In a metaphysical view of technology, genderless angels relate closely to genderless technology, but Barbarella and her persistent imagery has gendered space: a sexy barby doll seduced by men in the 60s, now becomes an empowered Blond in control as Kyle in her music-video, a space traveler with the mission to explore the « Expresso planet » and a feminist agent in the musical where Barbarella enters erotic relationships only with women, the angel Pygar and the robot Victor. By introducing sex in relation to the angel and technology, physical pleasure and the subject of the body is being applied on to metaphysical and technological ventures. Friedmar Apel has argued that the Romantic period at the turn of the 18th to the 19th century shows an embodiment of the senses and restauration of mythology in the appearance of angels in the arts, as a contra movement against the mechanisation and rationalisation of the world. The longing to reach the invisible, divine or transcendental has been infiltrated with a desire for love, eroticism and sexuality. Reviewing recent spiritualist movements and the broad popularity of the subject of angels, I join Apel in questioning if the beginning of the 3rd Millenium brings back a similar tendency, a desire to restore sacred spaces, esoteric knowledge and, as he calls it, a « Himmelssehnsucht ». [20]

The myth Barbarella suggests a constructive look into the infinite unknown and mysterious universe by applying love and awe instead of fear, against deterministic, destructive visions on alienated extraterrestrial space. The symptomatic reiteration and persistence of cultural phenomenon as in the case of Barbarella call for strategies of synthesis in order to reconfigure our understanding of popular imagination and to help finding new portals and bridges between academic discourse and the aspirations of contemporary popular culture.

The Plausibility of Space (David Surman)

I would like to conclude our collaborative presentation by proposing a number of core principles in the theorisation of space, popular culture and audience. The examples I take to illustrate my view express a particular involvement in the popular. Little effort was needed on my part to draw together the various instances shown here to illustrate the popular (albeit fictional) representation of space. Imaginary ‘outer’ space is everywhere.

As we have seen, in a large variety of cultural instances the expression of space exploration as a thematic, iconic or symbolic referent diverts drastically from the pioneer image of space exploration first popularised by Russian and American efforts. In the continuities and discontinuities of visual culture, it is reasonable to suggest that whilst there has been little modification of the image of space offered by popular science, the aesthetic modalities of science fiction have – in a sustained dialogue with its various audiences – developed a modus operandi quite distinct from its rationalist counterpart.

Of course, science-fictional representations of space precede any actual human intervention into that domain. In imagining ourselves there, our exploratory desires manifest in technologies capable of achieving our original speculation. Imagination, technology and desire constitute an interdependent cycle that affects and sustains our technological development.

It seems however when looking at the popular representation of imagined technology that such a paradigm is more complex than that. Desire, a constituent part of our elusive consciousness, is never focused in its entirety upon any one singular instance. Spiritual, technological and libidinal desires intermingle in the imaginary, and whilst rationalist science effaces the trace of such cross-pollinations, sciences popular imaginary enjoys the product of this meta-combination of influences.

The plurality of desires manifest in science fiction ensures its continuity, and accommodates a far larger range of interpretations than the rhetorical strategies of ‘popular’ science, which still expresses a modernist conception of its audience. In science fiction, the spectator is always prepared to meet the creator halfway, permitting lapses of rational coherence for the greater good of an affective experience that is continuous with both contemporary and prior comparable works.

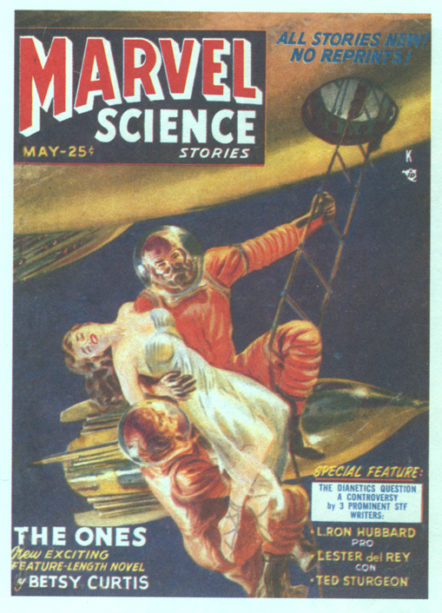

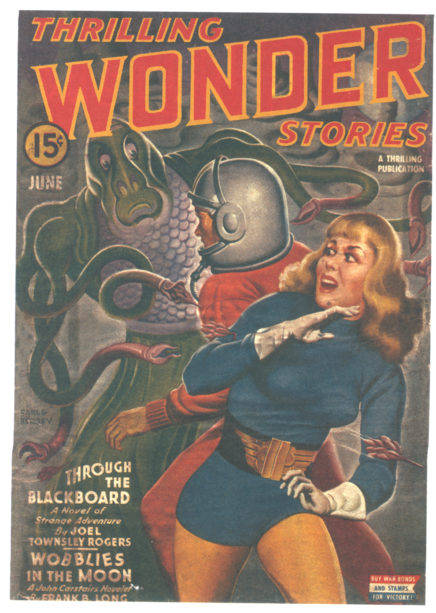

Consider for a second the layered desires that combine in the cover image of the May 1951 issue of Marvel Science [fig.1], a popular ‘pulp’ magazine of forties and fifties America. The sexuality of the Hollywood icon is idealised in the woman’s image, and she is carried into a space ship by two astronauts, dually representative of both science fact and fiction. All the while, she seems to not need a space suit in outer space. Another example of this surreal image of difference can be seen on the cover of the June 1941 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories [fig.2].

The representations of space in the cinema are characteristically divided between those which sustain the scientific rhetoric of technological development (Apollo 13, The Right Stuff) and those which utilize the environment of outer space to play out distinctly ‘earthly’ preoccupations. Steven Soderbergh’s recent remake of Solaris (2003) uses the master signifier of the space station to illustrate the fragility tragedy of earthly memory. Drawing an unbearable parallel between lost memory and the frustration of unknowable region of space, Soderbergh’s feature film uses the image of space as a potential future into which domestic frustrations are sustained.

How are these images culturally legitimated, when their irrationality seems so explicit as to debunk the value of their narrative content? And secondly, why are such desire-driven images so persistent in our visual culture? The film scholar Christian Metz developed a critical definition of ‘plausibility’ with which we may account for those images that persist in culture, compared to those that don’t. He writes, ‘the Plausible…is an arbitrary and cultural restriction of real possibles; it is in fact censorship; among all the possibles of figurative fiction, only those authorised by the previous discourse will be chosen. There is much to extract from this. The representation of space preceded the actuality of space exploration, in the early cinema of Méliès at the turn of the century and, even earlier, the humorous cartoons of nineteenth-century caricaturist Rodolphe Töpffer.

The moon landing and its subsequent realm of representation is scientifically plausible. And yet, should we set the cultural presence of this particular mode of representing space against that which we may broadly term science fiction, there is an unarguable predominance of fantastical imagery in our everyday domestic culture. The lure of the rational is nothing compared with the refined articulations of the imagined.

The irrationality of an image such as this ‘pulp’ magazine cover is not simply the expression of an uneducated comic artist. It represents the most persistent means of creating space as a plausible phenomenon, to the extent that it is even rendered domestic as in Solaris. The men, housed in their space suits, are accompanied by a woman who apparently has no need for such technological baggage. She is in her element. This principle of sexual difference is maintained in extraterrestrial representation in a host of varied instances, the female alien seducing/destroying the human as astronaut-explorer-imperialist.

Jane Fonda’s striptease at the beginning of Barbarella was recently imitated by the pop star Kylie Minogue in the video for put your self in my place. In the video Kylie similarly strips off a pink astronaut’s suit from the relative confines of her space station. Empowered by her technology, she blocks the gaze of the grey-suited male astronauts outside of her spaceship with a plume of smoke. The video is rendered ‘plausible’ by its continuity with Barbarella and the broader trends of science fiction. Difference articulates the desirability of the protagonist and provides a means to permit identification between audience and moving-image text.

For popular science to plausibly represent our ongoing role in space it must necessarily engage with a more sophisticated representational approach to space, one which locates difference at the core of the scientific imaginary. I would like to suggest that ‘difference’, that everyday determinant against which we develop our identity, is needed in the representation of space in popular science. The role of gender, sexuality, race, class, physical ability, even hair colour is necessary to the future plausibility of represented space.

Identification is a fiercely contested principle in the humanities, and there are vast tracts devoted to often opposing theories of how identification functions. Be it cognitive, psychoanalytic, and phenomenological or narratological, all theories of identification, and specifically those in film studies, locate difference as the core principle through which audience participants relate to the world of representation. All representation functions through the articulation of types, and yet the representation of the human in the space of popular science has been woefully devoid of difference, choosing instead to recall tenuous continuities to the (now distant) moon landing.

For popular science to plausibly represent our ongoing role in space it must necessarily engage with a more sophisticated representational approach to space, one which locates difference at the core of the scientific imaginary. Modernist accounts of the audience no longer account for the heterogeneity and complexity of mass culture. The realisation that the vast majority of space is unknowable echoes the topography popular imaginary, whose complexity has evaded scholarship since the sixties. It is however possible to observe the continuities and discontinuities; what is permitted to rehearse its codes and what is disavowed. In Metz’s terms, the most plausible of images, primarily those which recall our foundational experiences of difference, will presumably be those toward which popular science may move if it is to articulate its message in the vocabulary of the popular imaginary.

Notes

Editor’s Note: Some links from the original article are no longer valid. We have removed them. You can however find them in the original publication from 2004 archive.olats.org/space/13avril/2004/te_mPunt.html

[1] For further discussion of the relationship between space exploration and cinema see Michael Punt, Digital Media, Artificial Life, and Postclassical Cinema: Condition, Symptom, or a Rhetoric of Funding? In: Leonardo, Vol. 31, No. 5, pp. 349-356, 1998.

[2] Michael Punt and Robert Pepperell have expressed this triangular relationship in their model of technology-desire-imagination, three faculties that are interrelated and contingent: « The imagination is prompted by human desire to modify the world through technology, which in turn prompts desire ». In: Michael Punt and Robert Pepperell: The Postdigital Membrane: Imagination, Technology and Desire. Intellect, 2000, p. 25

[3] Amongst other, the Syrian monk Dionysius the Areopagite (6th century), a pagan philosopher, and the German abbess Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) have perceived visions filled with endless chores and hierarchies of angels, beings of light. An old Jewish notion in the bible yet mentions that God dwelt in ineffable darkness « …truly mystical darkness of unknowing » (Exodus 20:21). And Dionysos the Areopagite wrote in a letter: « The divine darkness is that ‘unapproachable light’ where God is said to live. » In: John Gage, Colour and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. Thames and Hudson, 1993, p. 60

[4] Since the first half of the fifth century, winged angels have been populating space throughout art history. Fritz Saxl suggests that the wings of Christianity’s angels go back to Greek mythological figures as Mercury, Iris but mainly Victory who also played a crucial role in Roman art. This pagan image has been infiltrated into Christian mythology to an extent that it even contradicted the original writings of the bible where angels had to present themselves for who they were, they otherwise were not recognizable as they looked human in their appearance. In: Fritz Saxl, A Heritage of Images. Middlesex: Peregrine, 1970, p. 22f

[5] Gilles Deleuze writes in this respect: « The whole of cinema can be assessed in terms of the cerebral circuits it establishes, simply because it’s a moving image. Cerebral doesn’t mean intellectual: the brain’s emotive, impassioned too… » in: Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations. New York: Columbia University Press, 1972-1990, p.60

[6] Edgar Morin has stressed the importance of processes of projection and identification, « cosmomorphism » and « anthropomorphism », which inoculate perpetually humanity into the exterior world and vice versa. Edgar Morin : Le Cinema ou l’Homme Imaginaire: Essay d’Anthropologie. Les Editions de Minuit, Paris, 1956

[7] Robert D. Romanyshyn: Technology as Symptom and Dream. London/New York, Routledge, 1989, p. 44 Similarly, dark matter functions not only as screen but turns itself into a projection into our internal imagination, through a look inside, our internal space consumes its own representation, an image to which Michael Punt has referred to in his introduction showing the clip « The big swallow » by James Williamson (Brighton, 1900).

[8] A famous example is the German physicist Wernher von Braun’s collaboration with the Walt Disney’s television programs about space in the mid 50ies: Man in Space, Man and the Moon and Mars and Beyond. According to David R. Smith, director of the Walt Disney’s archive, President Dwight Eisenhower requested « Man in space » to run it for important audiences in the Pentagon in March 1955. Four months later, Eisenhower announced plans to launch the first satellite. Von Braun’s remark to the producer of the series to this apparently has been: « They’re following our script ». Eugene S. Ferguson: Engineering and the Mind’s Eye. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London: MIT Press, 1992, p.2

[9] Several media theorists including Marshall McLuhan have argued that the moon landing as media-spectacle dominates the question if it has actually taken place or not. This notion links up with postmodernist theories, like Jean Baudrillard’s concept of the hyperreal and the fact that people’s imagination demands the real thing, but in order to get it, they have to create fakes. In: Jean Baudrillard: Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994

[10] In recent years, the senses have been re-introduced most prominently into science, and since feminist perspectives have entered scientific discourse and artists work relates more closely to scientific research, the faculty of the body cannot be denied any longer. Technology and spirituality have both shown a tendency to neglect the body in the past, contemporary discourses ask for a reconsideration and restoration of the union and interrelation between body and mind.

[11] Directed by Dino de Laurentis alias Roger Vadim, husband of actress Jane Fonda (Barbarella)

[12] Directed by Kim Duddy, Music by Dave Stewart, Premiere in March 2004 at the Raimund Theatre in Vienna.

[13] The September/ October image for instance shows a robot constructed by white espresso cups on the « expresso planet », holding the 2004 blond Lavazza-girl in its arm, evoking images from the movie Barbarella in contrast to white male astronauts in white suits on an extraterrestrial mission. Jean Hugues de Chatillon (set design) says: « …she’s got charisma (the model Ingrid Parewijck), a strong character, such blonde hair… her presence is classic but extremely elegant and a bit adventurous. I see her as the Barbarella of the future Lavazza world, who is astonished as she goes out to discover the world… » He also expresses the mysteriousness of black coffee as analogy to black space: « …For the choice of the scenes I tried to approach the essence of coffee, which is a dark and soluble substance burnt by the sun and by fire. »

[14] Quote from the « love-protector » by Haus-Rucker-Co. In: Dieter Bogner, Haus-Rucker-Co: Denkräume – Stadträume 1967-1992, Ritter Verlag, Klagenfurt, 1992. The exhibition « The Austrian Phenomenon » includes the architects Raimund Abraham, Domenig/Huth, Haus-Rucker-Co, Coop Himmelb(l)au, Bernhard Hafner, Hans Hollein, Missing Link, Zünd up, and more. Some of Haus-Rucker-Co’s projects names are: « Phy-Psy, Balloon for Two, Connexion Skin, Pneumatic Living Cells or Air-Unit, Mind-expander, Pneumacosm, Flyhead, Viewatomizer, Drizzler, Electric Skin, Environment Transformer, Roomscraper, Battleship, Yellow Hear, Vanilla future ».

[15] To give another example that relates science fiction literature and film, in the context of slash subculture, Constance Penley has shown how amateur (mostly female) writers have subverted and rewritten Star Trek to incorporate their own sexual and social desires. In: Constance Penley, NASA/TREK: Popular Science and Sex in America. London/New York: Verso, 1997.

[16] Domestic issues about living in space are been addressed by the European Space Agency in their feature « Daily life » at http://www.esa.int/, which comments on the complication of daily operations like dressing in a zero-gravity environment. Star Trek: The Next Generation, by Gene Roddenberry, 1987-1994. See www.startrek.com

[17] Inhabitants of the planet pluck Pygar’s wing’s feathers as if they were merely a costume and Barbarella reanimates Pygar by moving it’s wings, rather than following the Dark Queen’s advice to do a « mouth to mouth ». This does not seem to bother Pygar, whereas in other fictionalised accounts in literature, the wings are often presented as an angel’s integral part of the body, being extremely sensitive to touch (Samara Trilogy by Sharon Shinn, 1997-99), sometimes a highly erogenous area (The Vinter’s luck by Elizabeth Knox, 2000). Furthermore, Barbarella takes Pygar by its hand (as the player does in the Video Game Icon) and pulls it behind her, treats it like a toy. A sexual toy, and its maleness itself is linked to technology when Barbarella sneaks her revolver into its feather pants.

[18] With a similar spirit, Cyborgs of the 21st century that loose control are conquered or humanised and restored by love, as it is most prominently at stake in Japanese Animee: Chôjikû yôsai Macross: Ai oboeteimasuka by Noboru Ishigure and Shôji Kawamori (1984), Akira by Katsuhiro Ômoto (1988), FLCL by Kazuya Tsurumaki (2000), Metoroporisu by Rintaro, based on Osamu Tezuka’s comic (2001), Cardcaptor Sakura by Clamp (2001).

[19] « Himmelssehnsucht » is difficult to translate, is expresses a longing for the « heavenly realms », while « Himmel » in German means both the sky and heaven. Therefore this expression could also be translated to human’s engagement with space exploration. In: Friedmar Apel, Himmelssehnsucht: Die Sichtbarkeit der Engel in der romantischen Literatur und Kunst sowie bei Klee, Rilke und Benjamin. Paderborn: Igel-Verlag, 1994.

[20] Metz, C. 1974. Film Language. New York: Oxford University Press. 239.

© Michael Punt, Martha Blassnigg & David Surman & Leonardo/Olats, may 2004, republished 2023.

Leonardo/Olats

Observatoire Leonardo des Arts et des Techno-Sciences

À propos / About | Lettre d'information Olats News

Pour toute (re)publication, merci de contacter / For any (re)publication, please contact Annick Bureaud: info@olats.org

Pour toute question concernant le site, merci de contacter / For any issue about the website, please contact: webmaster@olats.org

Design Thierry Fournier

© Association Leonardo 1997-2022